BOOK REVIEW THE STALIN AFFAIR

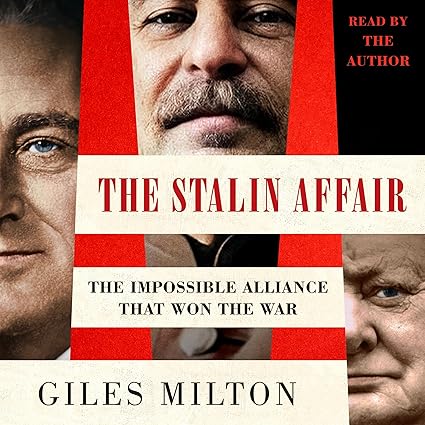

The Stalin Affair: The Impossible Alliance That Won the War

By Giles Milton

Book review by Paul A. Myers

This is a crackling good read and a top contender for best history of the Second World War published this year. It is an epic story of diplomacy at the highest level for the most consequential of stakes—ultimate victory or the abyss of blackest defeat. The balance point of the story is how two top diplomats, one American and one British, forged and sustained the relationships between three men—Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt—that kept the countries of Russia, Britain, and the United States in alliance to defeat the common enemy, Nazi Germany. The story crackles with the verve of you-are-there storytelling of the rise and fall of interpersonal relations.

The key to defeating Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany and winning the Second World War was to maintain unity between Russia and the two western allies, the United States and Britain. That the near-unanimity between the dictatorship and the two western democracies was sustained into 1945 was near-miraculous. The blood of victory was a massive supply of western arms, munitions, and materials provided by the western allies, fought through by brave merchant ship convoys across cold Arctic seas and through the often boiling hot Persian Gulf, then across Iran, and into southern Russia. The centrality of the supply effort to the ultimate victory is made succinctly clear and dramatizes the great role played by the American economy in what was a worldwide effort. Roosevelt’s Arsenal of Democracy delivered; Russian Lend Lease was one of the great triumphs of the revved-up American enterprise economy.

Russia was led by a communist dictator, Joseph Stalin, while the western allies were led by two formidable democratic leaders, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. This unprecedented effort at collaboration between political polar opposites was mediated by two extraordinary ambassadors, Archibald Clark Kerr (“call me Archie”) for the British and Averell Harriman for the United States. Key accounts are provided in the letters of Harriman’s daughter, Kathy, who had a singularly close role to the great events.

The focal point of the narrative is Moscow. Two dramatic peaks in the narrative are the Big Three meetings of the leaders at Tehran in the fall of 1943 and Yalta in early 1945. Big decisions are reached at both. Both conferences remain controversial to this day.

To bring into focus Roosevelt’s long-standing commitment to internationalism, one of the last chapters of the book explains the president’s hope to “make the Soviet Union a formal player in the postwar international order … This had long been Roosevelt’s geopolitical dream. It had motivated him ever since America’s entry into the Second World War.” This über-objective should be kept in mind as one watches Roosevelt’s efforts to encourage Stalin towards a cooperative stance about the postwar peace throughout the war. Roosevelt’s intractable critics were never charitable on this point during the war or after because they have never shared the goal or the vision. But what the Paris Peace Treaty of 1919 had shown was that the democracies could lose the postwar peace even while winning a war. Roosevelt was determined to do better.

Other fascinating high points are Winston Churchill’s three trips to Moscow to confer with Stalin in 1942, 1944, and 1945. These trips posed unique challenges to Harriman who had to effectively represent Roosevelt and America’s interests in meetings where he was not always present. Churchill, always the arch-imperialist, tried to advance power-sharing schemes with Russia for sustaining British imperial power after the war, goals explicitly not acceptable to the Americans who envisioned a postwar world that would be post-imperial, multilateral, and respectful of national self-determination if not always the democratic aspirations of the people.

Churchill’s sense of great power importance was deeply wounded by Stalin’s provocative gibes about Britain’s waning power, a weakness against which Churchill struggled throughout the war. Accordingly, British ambassador Archie Clark Kerr had an even greater challenge than Harriman in 1942 when it came to keeping Churchill’s fledging personal relationship with Stalin on track in the face of Stalin’s provocations and Churchill’s sullen and angry responses. The 1942 meeting in Moscow came perilously close to collapse, threatening the entire enterprise. The 1942 meeting also graphically illustrated the difficulties that all of Churchill’s immediate aides had in managing their own relationships with the mercurial and often recklessly adventuresome British prime minister throughout the war. This was in marked contrast to the smoothly functioning American high command that Roosevelt assembled before and during the war, which functioned with corporate-like smoothness.

Beneath the narrative is a story of power and the vital necessity of putting first things first in the ruthless arena of hard choices. The Americans grasped the absolutist nature of Stalin’s autocratic exercise of power, its uncompromising nature. The Americans also stayed clear-eyed about rank ordering priorities so that the most important came first. Roosevelt aimed to win the war and then to successfully construct a new postwar order of multilateralism that included all the global powers; none were to be left out, the great defect of the post-World War I peace agreement which included neither defeated Germany nor out-casted Bolshevik Russia.

Roosevelt and the American high command were committed to defeating Germany first and Japan second and saw that defeating Germany was best accomplished by Russia attacking from the east and the allies attacking from the west. The American army chief of staff General George C. Marshall was a constant and strong voice for the assault in northwest Europe and was supported in this objective by Roosevelt in 1943-44. Churchill in contrast advocated a near never-ending stream of peripheral operations in southern Europe that supported the security of Britain’s lifeline through the Mediterranean to India and its east-of-Suez empire. The Americans considered Britain’s postwar imperial pretensions as being distractions to the central goal of timely defeat of Germany in north-central Europe. Churchill saw them as central to his postwar vision of a renewed British Empire. This conflict in strategic visions oriented around advancing on quite different geographical axes created tensions in the British-US relationship throughout the war. So the British and Americans often diplomatically approached Russia from different starting points and perspectives. Both ambassadors were constantly reconciling differences among their principals’ respective goals. But American economic power always gave it the last word and Harriman played that card skillfully.

The history opens with the German invasion of Russia on June 22, 1941. Winston Churchill quickly responds to the event and addresses the British public on radio that first evening pledging to go to Russia’s aid. In Washington, the Americans stay quiet; they are divided. Some Americans see the inevitability of joining Britain in the war; most want to stay out of the war. The reader is there and sees this with his or her own eyes.

Four months earlier on March 7, 1941, during the darkest of bleak times in democracies’ war fortunes, Roosevelt had hosted for lunch the rich and stylish Averell Harriman, reportedly the fourth richest man in America, and offered him a position of what Harriman understood was to be the role of a lifetime—special representative of the president to the British prime minister with a charge to keep Britain in the war. Harriman was offered a central role at the heart of the highest allied war councils from the start, a place he would occupy for the next five years. Harriman’s aide Bob Meiklejohn kept a detailed diary of these years while Harriman’s daughter Kathy wrote many detailed letters over this period. Both sets of documents only fully came out of the archives decades later, many are used in this history for the first time. Churchill’s youngest daughter Mary also kept a diary of these years and she too was a confident of Kathy Harriman.

Harriman departed for London shortly thereafter, the journey that launches the larger tale. His daughter followed several weeks later but not before Averell had started an affair with the twenty-one-year-old Pamela Churchill, the prime minister’s daughter-in-law, in the wake of a big soiree held in the swank Dorchester Hotel during a Nazi bombing raid. The two young women become friends but never discuss with each other their shared secret about the affair. The two women keep up their correspondence when the Harrimans move on to Moscow

The story of the crucial Russian alliance with the western democracies is told against the panoramic backdrop of the Second World War. The war’s insistent demands buffet the top leadership at each critical juncture of the war. The narrative highlights the central directing role the top levels of civilian leadership play in the US and Britain; generals and admirals are in supporting positions, executors of but not authors of high strategy. In particular, one can see that the civilians controlled the big strategic decisions of the war and that Roosevelt in particular kept his eye on the postwar world he hoped to see come out of the conflict. Churchill constantly meddles in military matters; Roosevelt rarely.

The larger story of east-west alliance kicks off with the German invasion of Russia in June 1941. There is an excellent and timeless description of Stalin as the absolute dictator. He is described as a man of terrifying ruthlessness towards any potential challenger. The power maintenance technique involves surrounding himself with mediocrities and employing iron discipline to sustain a position of absolute despotism.

Shortly after the invasion the British delegation sign an historic Anglo-Soviet agreement that provided first for mutual assistance in the war against Hitler and second that neither country would sign a separate peace with Nazi Germany. As for the first, Russia complained about the inadequacy of the supply throughout the war—huge supplies were never enough—and as to the second it carefully watched for any signs of dalliance with the Germans by the western allies, who themselves also feared a second August 1939 style Russo-German pact. All eyes were always on the diplomatic poker table during this period of transactional cooperation and deep mistrust.

To cut to the chase, the narrative progresses with great panoramic views of the major events of the war leading up to the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945 and the United Nations conferences at the end of the war. Stalin had pulled Russia out of participation in the conferences sometime after Yalta despite pledging at Yalta to attend, a withdrawal deeply disappointing to Roosevelt and Churchill. The allies were rapidly growing apart. Roosevelt sent an extremely conciliatory letter to Stalin and Harriman was asked to deliver it. Instead, Harriman, deeply concerned about rapidly decomposing relations with Russia, sat on the letter and sent a telegram back to the State Department urging a change in policy. But before action could be initiated news or Roosevelt’s death arrived.

News of Roosevelt’s death sets the stage for a poignant turning point in Moscow. Upon hearing of Roosevelt’s death, Stalin commiserates with Harriman expressing his deeply sympathetic condolences. Harriman sees an opportunity in Stalin’s rare display of sympathy to urge the Russian leader to reconsider about the United Nations and dispatch Foreign Minister Molotov to San Francisco for the upcoming United Nations talks. Stalin momentarily reflects and then agrees, securing Russian’s participation in the United Nations. This makes the new international body a true great power forum of all the world’s leading powers. Roosevelt’s great vision for the postwar world is realized and the victory in the war at least provides an institutional framework for a more collaborative postwar future, an aspiration ultimately not fully achieved.

The book concludes with an Afterlives chapter that summarizes the rise of postwar tensions and the start of the Cold War. It concludes by summarizing the Big Three alliance: “Against all the odds, it had won the war for the Allies. But it was unable to survive the peace.”

1 thought on “The Stalin Affair – Mission to Moscow”